In a groundbreaking study published in Nature Communications in 2026, researchers have unveiled a previously underappreciated climatic feedback mechanism linking extreme precipitation events to significant decreases in sea-air carbon dioxide (CO₂) fluxes in the South Pacific and South Atlantic Oceans. This discovery not only reshapes our understanding of ocean-atmosphere carbon interactions but also raises critical questions about the global carbon cycle amid intensifying weather extremes propelled by climate change.

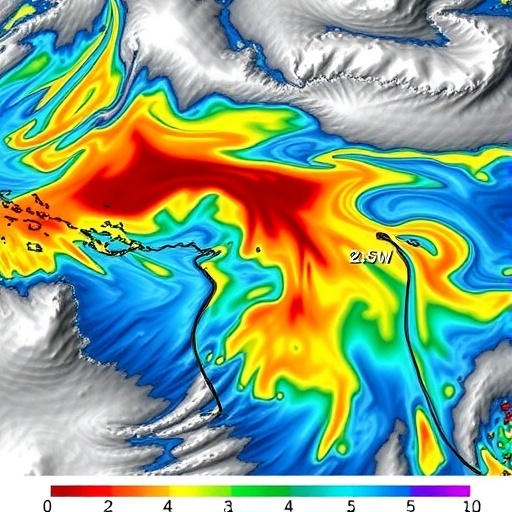

The research team, led by Li, Liu, Dong, and collaborators, employed advanced observational datasets and coupled Earth system models to investigate how episodic, anomalously intense rainfall influences CO₂ exchange between the ocean and atmosphere. The focus on the South Pacific and South Atlantic regions stems from their unique oceanographic and climatic characteristics, serving as crucial zones for oceanic carbon uptake that directly influence atmospheric CO₂ concentrations. By integrating satellite remote sensing, in situ measurements, and modeled simulations, the study paints a comprehensive picture of the multifaceted processes underpinning the observed carbon flux alterations.

At the heart of the phenomenon lies the interplay between precipitation-induced changes in ocean surface salinity, temperature stratification, and biogeochemical dynamics. Extreme precipitation events inject vast amounts of freshwater into the ocean surface, leading to pronounced stratification and altering the vertical mixing regimes essential for the transport of CO₂-rich waters to the atmosphere. This enhanced freshwater lens effectively caps the ocean surface, reducing the upwelling of dissolved inorganic carbon from deeper layers and consequently diminishing the outgassing of CO₂.

Moreover, the freshwater influx impacts the marine carbonate system by diluting surface water alkalinity and modifying pH levels. The altered chemical equilibrium reduces the partial pressure difference of CO₂ between the ocean and atmosphere, which is the primary driver of air-sea gas exchange. This chemical feedback exacerbates the physical effects of stratification, collectively culminating in a substantial decrease in CO₂ emission fluxes from these oceanic regions during and following extreme precipitation episodes.

The research delineates that these precipitation-driven reductions in sea-air CO₂ fluxes are transient yet have the potential for cumulative impacts. As climate models project an amplification in the frequency and intensity of extreme rainfall events, the modulation of marine carbon exchange by such episodic processes could introduce nonlinearities into the global carbon budget. This insight challenges the prevailing assumption that oceanic carbon fluxes respond smoothly to long-term warming trends and highlights the importance of incorporating extreme weather variability in climate-carbon modeling frameworks.

One pivotal aspect of the study is its methodological innovation in capturing the temporal and spatial complexity of these events. The researchers utilized high-resolution satellite data from missions such as SMAP and GPM to quantify surface salinity fluctuations and precipitation patterns with unprecedented precision. Coupled with autonomous floats equipped with biogeochemical sensors, the team directly observed stratification changes and carbon system parameters before, during, and after extreme precipitation. These empirical observations formed the validation basis for Earth system model experiments that disentangled the relative contributions of physical mixing alterations and chemical buffering to CO₂ flux changes.

A key finding reveals regional disparities in the magnitude and duration of CO₂ flux suppression. The South Pacific exhibited more prolonged reductions tied to persistent freshwater lenses driven by monsoonal rainfall patterns, whereas the South Atlantic’s responses were sharper but shorter-lived, influenced by episodic tropical storms. This spatial heterogeneity underscores the necessity for region-specific modeling approaches considering local meteorology, oceanography, and ecosystem characteristics to accurately predict carbon cycle responses under evolving climate regimes.

The study also illuminates the secondary ecological consequences of altered precipitation and carbon fluxes. Reduced CO₂ outgassing influences local acid-base chemistry, potentially impacting phytoplankton communities that form the base of the marine food web. By disrupting these fundamental processes, extreme precipitation events may cascade effects through trophic levels, affecting fisheries and biogeochemical feedbacks to climate. Although the authors call for focused biological studies, their initial findings hint at complex interactions between physical climate extremes and ocean biology that warrant urgent attention.

Furthermore, the researchers pinpoint potential feedback loops whereby weakened CO₂ emissions from the ocean surface could transiently enhance atmospheric CO₂ accumulation, thereby fueling further warming and intensifying the hydrological cycle. This storyline adds nuance to the carbon-climate feedback narrative, suggesting that extreme precipitation not only modulates carbon fluxes locally but might also influence global climate trajectories in nontrivial ways.

This research injects fresh urgency into international climate discourse, especially regarding projections of the Earth system’s capacity to buffer anthropogenic emissions. The emergent picture reveals that the ocean’s role as a carbon sink may be more vulnerable to climatic variability than previously thought, particularly as extreme weather patterns become increasingly frequent. Policymakers and climate modelers must grapple with these nonlinear, episodic effects to devise robust mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Importantly, the authors advocate for expanded observational networks focusing on the intersection of extreme weather events and biogeochemical cycles. They emphasize the potential of next-generation satellites and autonomous platforms to fill critical data gaps, enabling dynamic monitoring of these rapid, high-impact processes at ocean-atmosphere boundaries. Such enhanced capability will be instrumental in refining Earth system models that underpin global climate policy.

While the study advances frontiers in understanding, it also acknowledges limitations, notably the challenges in simulating complex precipitation dynamics and their heterogeneous oceanic impacts across spatial scales. The researchers call for cross-disciplinary collaborations combining meteorology, physical oceanography, and marine chemistry to unravel the mechanistic details that remain elusive. This interdisciplinary approach promises to unlock new insights into the feedback mechanisms that mediate planetary carbon flows.

The implications of these findings extend beyond the scientific community. Coastal nations bordering the South Pacific and South Atlantic stand to experience altered ecosystem services and fisheries productivity linked to fluctuating ocean carbon states. This socio-ecological dimension adds a human element to the study, highlighting that extreme precipitation effects on ocean carbon cycles have tangible consequences for livelihoods and food security.

Ultimately, this research offers a critical reminder that climate change manifests through complex, interacting pathways where extreme events impose outsized influence on foundational Earth processes. The intricate dance between freshwater input, ocean stratification, and carbon chemistry underscores the fragile balance sustaining the global climate system. By elucidating these connections, this study equips humanity with the knowledge to better anticipate and respond to future climatic uncertainties.

As atmospheric CO₂ levels continue to rise and the hydrological cycle grows increasingly erratic, the importance of understanding episodic phenomena such as precipitation-driven CO₂ flux changes cannot be overstated. This study pioneers this frontier, marking a vital step toward a holistic grasp of ocean-atmosphere carbon dynamics in a rapidly changing world. Its insights will resonate across climate science, policy frameworks, and environmental stewardship efforts for years to come.

Subject of Research: Ocean-atmosphere carbon dioxide fluxes and the impact of extreme precipitation on the South Pacific and South Atlantic regions.

Article Title: Decreases in South Pacific and South Atlantic sea-air CO₂ fluxes caused by extreme precipitation.

Article References:

Li, Z., Liu, H., Dong, X. et al. Decreases in South Pacific and South Atlantic sea-air CO₂ fluxes caused by extreme precipitation. Nat Commun (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-69847-6

Image Credits: AI Generated