In a groundbreaking study published in Nature Geoscience, researchers have unveiled an unprecedented reconstruction of warm-season temperatures and vegetation changes in South Siberia, spanning the last 8.6 million years. Centered on Lake Baikal, the world’s deepest freshwater lake, this comprehensive palaeoclimate record provides vital insights into Earth’s climate system feedbacks and the complex interactions between ecosystems and regional temperature fluctuations during the Neogene and Pleistocene epochs.

Long recognized as a vital archive of climatic history, Lake Baikal’s sediments contain detailed information about past environmental conditions. This latest research employed state-of-the-art analytical techniques to extract and analyze palaeobotanical remnants, including pollen and plant macrofossils, offering a direct window into ecosystem evolution across vast geological timescales. The data elucidates a gradual cooling trend throughout the late Neogene period, culminating in a pronounced ecological and climatic shift approximately 2.7 million years ago.

This critical transition marks the onset of the Early Pleistocene and is characterized by a sudden shift toward severe cold conditions during glacial intervals. The study reveals that prior to this epoch, the region supported predominantly forested landscapes. However, as the climate plunged into colder phases, the dominance of forests was progressively supplanted by expansive steppe–tundra ecosystems. These vegetational changes are indicative of increasingly harsh environments, likely influenced by a southward expansion of permafrost zones into areas previously conducive to forest growth.

Pivotal to understanding these transformations is the quantification of temperature changes during glacial cycles. The team reconstructed the warm-season paleotemperatures and documented stark cooling events aligned with glacial periods. The temperature minima during Early Pleistocene glaciations intriguingly resemble those observed during the more recent Late Pleistocene, despite substantially warmer global mean temperatures earlier on. This paradox highlights the nonlinearity of regional climate responses to global forcings and underscores the complexity inherent in Earth’s climate system.

Beyond the direct climatic conditions, the shift from forested to open steppe tundra ecosystems bears significant implications for Earth system feedbacks related to albedo and carbon cycling. Forests typically have a lower albedo, absorbing more sunlight, while open tundra and steppe landscapes reflect more solar radiation back into space. This alteration in surface albedo could have contributed to reinforcing and amplifying regional cooling trends, thereby perpetuating a feedback loop that intensified glacial conditions.

Moreover, the expansion of permafrost into South Siberia likely played a crucial role in carbon storage dynamics. Permafrost soils represent vast reservoirs of organic carbon, and their extent influences the carbon balance between the terrestrial biosphere and the atmosphere. The freezing and thawing cycles of permafrost can release or sequester greenhouse gases, thereby modulating atmospheric composition and further influencing climate patterns.

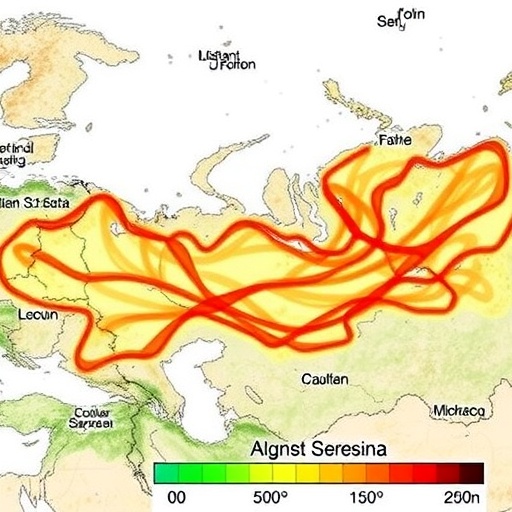

The study’s comparative review of palaeobotanical data across the Arctic and subarctic regions suggests that this ecosystem turnover was not an isolated phenomenon but instead represented a broader biogeographic response to climatic shifts spanning the high northern latitudes. Nevertheless, the detailed temporal resolution achieved in South Siberia offers unique insights into the pace and abruptness of these changes, which remain less resolved in other regions.

This research substantially advances our understanding of how terrestrial ecosystems and climate interacted during a pivotal phase of Earth’s history. The Early Pleistocene marks a critical juncture when glacial–interglacial cycles intensified, shaping the planet’s physical and biological systems. By documenting these regional responses with high precision, the study challenges the conventional narrative that average global temperatures alone dictate ecosystem and regional climate dynamics.

Importantly, the researchers highlight the synergistic effects of multiple feedback mechanisms, including vegetation-albedo interactions and permafrost carbon storage, which likely operated alongside well-established oceanic and ice sheet feedbacks. These complex interdependencies underscore the necessity of integrating terrestrial processes into climate models to faithfully capture long-term climate variability and predict future trajectories.

This nuanced understanding bears relevance for contemporary concerns relating to climate change. As modern-day warming threatens to destabilize permafrost zones and alter vegetation patterns across Siberia and the Arctic, insights drawn from deep-time climate records can inform expectations of potential feedbacks that may exacerbate or modulate ongoing warming.

The sophisticated proxy reconstructions from Lake Baikal also serve as benchmarks against which climate model simulations can be tested and refined. Improved modeling fidelity is crucial for projecting the influence of terrestrial feedbacks on future climate scenarios, particularly in mid- to high-latitude regions where land–atmosphere interactions exert profound influences.

Furthermore, by elucidating periods of abrupt cooling and ecosystem turnover, the study enriches our understanding of Earth system resilience and thresholds. Recognizing when and how ecosystems undergo rapid transformations can help anticipate tipping points and guide strategies for mitigating ecological consequences under accelerating environmental change.

The research team’s interdisciplinary approach, combining palaeobotany, geochronology, and climatology, exemplifies the integrative science required to disentangle the multifaceted components of Earth’s climate history. The long, continuous sedimentary record from Lake Baikal provides a rare and invaluable archive critical for reconstructing these past climates with exceptional temporal depth and resolution.

As the scientific community continues to unravel the factors governing climate sensitivity and feedbacks, this study stands as a landmark contribution to palaeoclimate science. It affirms the profound influence of regional terrestrial systems in shaping past climate regimes and emphasizes their potential to amplify or dampen global climate signals through complex feedback loops.

Ultimately, this comprehensive study not only deepens our knowledge of Siberian palaeoecology and climate dynamics but also reinforces the urgency of understanding terrestrial contributions to climate feedbacks in an era of rapid anthropogenic change. It advocates for enhanced observational and modeling efforts focused on land and permafrost systems to anticipate and mitigate future climate impacts.

The unprecedented data set and interpretive framework established herein pave the way for future investigations targeting the interactions between vegetation, permafrost, and climate on millennial to million-year timescales. Such insights are indispensable for reconstructing Earth’s climate evolution as well as informing policy and conservation efforts in vulnerable polar and subpolar regions.

By revealing how ecosystems and climate have co-evolved during periods of significant environmental stress, this work contributes a critical piece to the puzzle of Earth’s dynamic climate system. It underlines that regional factors and feedbacks act as force multipliers, dictating the amplitude and pace of climatic transitions in ways that global averages alone cannot predict.

The findings presented in this study herald a paradigm shift in palaeoclimate research, urging a more holistic view that integrates multiple Earth system components and feedbacks. This approach holds promise for advancing climate science, ensuring more accurate reconstructions of the past and improved forecasts of a rapidly changing planet’s future.

Subject of Research:

Palaeoclimate reconstruction and terrestrial ecosystem responses to Late Neogene and Early Pleistocene climatic changes in South Siberia.

Article Title:

Early Pleistocene ecosystem turnover in South Siberia linked to abrupt regional cooling.

Article References:

Novak, J.B., Prokopenko, A.A., Tarasov, P.E. et al. Early Pleistocene ecosystem turnover in South Siberia linked to abrupt regional cooling. Nat. Geosci. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01914-x

Image Credits: AI Generated