In a fascinating exploration of cognitive processes, recent research has delved into the intricate mechanisms of divided attention, specifically concerning the perception of faces. Our brains are constantly bombarded by a plethora of visual stimuli, making the ability to focus on relevant information paramount for our daily functioning. However, this focus is not without its costs, particularly when we attempt to divide our attention among multiple subjects. A groundbreaking study conducted by Lee and Strother, published in the journal “Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics,” sheds light on how divided attention can lead to lateralized costs that affect our processing of faces, an essential component of social interaction.

The researchers embarked on their investigation by examining the neurocognitive aspects of facial recognition and attention allocation. Faces are not just objects; they are pivotal for social communication, conveying emotions, identities, and intentions. The ability to recognize and interpret facial cues with accuracy can influence our interpersonal relationships and overall social functioning. Yet, when our attention is divided, how do these abilities falter? Lee and Strother sought to answer this pivotal question.

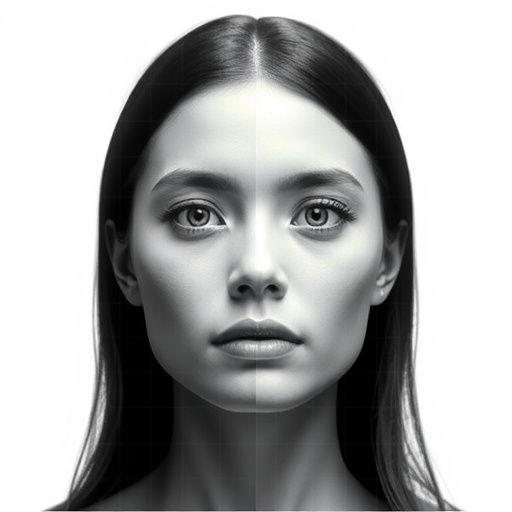

Through a series of meticulously designed experiments, the team explored how dividing attention impacts face recognition across different visual fields. Participants were presented with faces in a controlled environment, where their task involved recognizing and responding to faces while maintaining awareness of distracting stimuli. The results illuminated a clear pattern: participants struggled significantly more with face recognition tasks when their attention was split between multiple sources of information. This decline in performance was not uniform; rather, it revealed lateralized costs that varied depending on the side of the visual field being focused on.

One salient finding of the study was the pronounced cost associated with left visual field processing. When participants were required to divert their attention to the left, their ability to correctly identify faces diminished, highlighting a dominant effect of lateralization in attention. This finding aligns with existing neuropsychological literature suggesting that the right hemisphere of the brain, which primarily processes information from the left visual field, plays a crucial role in facial recognition. When divided attention was demanded, it seemed that the cognitive load overwhelmed the system, causing difficulties in processing crucial social cues.

The implications of such findings extend beyond the laboratory. In everyday life, individuals frequently deal with distracting environments, such as crowded places or busy social gatherings. For instance, when attempting to engage in conversation while being surrounded by other people, one might find it challenging to follow the subtleties of the facial expressions of those speaking. The study’s outcomes suggest that the brain’s struggle with divided attention may lead to misinterpretations of social signals, potentially resulting in misunderstandings or miscommunications.

Moreover, these divides in attention are not merely academic concerns. In negotiation contexts or social interactions where emotional intelligence plays a key role, being unable to accurately gauge a partner’s facial cues could impact the outcomes of discussions or collaborations. As people become increasingly reliant on multitasking, understanding how attention is divided can offer insights into improving social competencies and navigating complex social scenarios.

Lee and Strother’s research also opens avenues for further investigation into the neurobiological underpinnings of attention. The relationship between attention and the lateralization of cognitive processing invites questions about the brain’s architecture. The findings suggest that increasing attention resources to one side may fortify facial recognition abilities, where individuals can enhance their social perceptiveness, particularly in high-stakes environments or emotionally charged situations.

Mitigating the effects of divided attention is now an area ripe for exploration. Can training programs or interventions be developed to sharpen our focus on facial recognition in environments replete with distractions? Lee and Strother themselves hint at this potential in their conclusion, urging future research to explore strategies that may bolster face recognition skills even when attention is not singularly focused.

As the world becomes ever more interconnected yet paradoxically distracted, understanding how we can better appreciate our social surroundings becomes crucial. Whether it be through virtual interactions, such as video calls, or in-person engagements, our ability to perceive and interpret faces not only shapes our understanding of others but also ultimately enriches our human experience.

The study, while providing a robust framework for understanding divided attention, also emphasizes the need for continued exploration into its impact on cognitive processes. As technology continues to permeate our lives, creating environments with simultaneous information channels, it becomes increasingly important to grasp how our brain navigates these challenges.

Interestingly, the lateralized costs highlighted in Lee and Strother’s findings may have broader implications in clinical psychology as well. Disorders characterized by social perception deficits, such as autism spectrum disorder, may exhibit altered attention mechanisms towards faces. Could the principles uncovered in this research inform therapeutic strategies that enhance social cognitive skills in such populations?

Ultimately, the work of Lee and Strother has provided invaluable insights into how divided attention affects our interaction with faces, a fundamental aspect of human communication. By illuminating the costs associated with lateralized attention to faces, this research not only contributes to the field of cognitive psychology but also has the potential to inform practical applications that enhance our engagement with the world and with one another.

These findings remind us of the complexity of our cognitive processes and the continuous adaptability of our brains. As we endeavor to navigate our social worlds more effectively, acknowledging and understanding the costs of divided attention can lead to richer interactions and ultimately foster deeper connections within our communities.

In conclusion, Lee and Strother’s exploration into the lateralized costs of divided attention opens the door for many critical discussions, emphasizing not just the science behind attention and perception, but the profound impacts on social functioning and human connection.

Subject of Research: Divided attention and facial recognition

Article Title: Lateralized costs of divided attention to faces

Article References:

Lee, S.C., Strother, L. Lateralized costs of divided attention to faces. Atten Percept Psychophys 88, 38 (2026). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-025-03189-1

Image Credits: AI Generated

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-025-03189-1

Keywords: Divided attention, facial recognition, cognitive psychology, visual perception, social interaction.