The bottom of the ocean is not hospitable: there is no light; the temperature is freezing cold; and the pressure of all the water above will literally crush you. The animals that live at this depth have developed biophysical adaptations that allow them to survive in these harsh conditions. What are these adaptations and how did they develop?

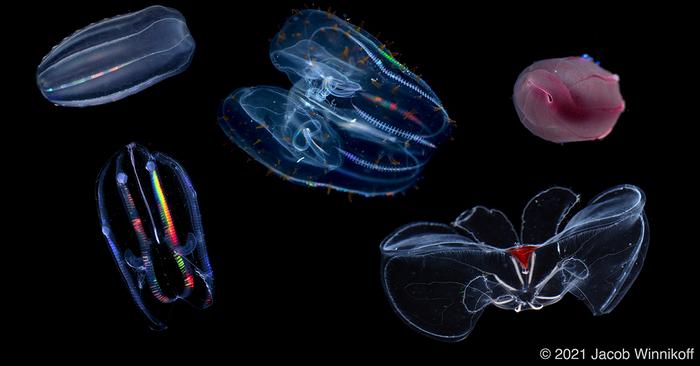

Credit: 2021 Jacob Winnikoff

The bottom of the ocean is not hospitable: there is no light; the temperature is freezing cold; and the pressure of all the water above will literally crush you. The animals that live at this depth have developed biophysical adaptations that allow them to survive in these harsh conditions. What are these adaptations and how did they develop?

University of California San Diego Assistant Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Itay Budin teamed up with researchers from around the country to study the cell membranes of ctenophores (“comb jellies”) and found they had unique lipid structures that allow them to live under intense pressure. Their work appears in Science.

Adapting to the environment

First things first: although comb jellies look like jellyfish, they are not closely related. Comb jellies comprise the phylum Ctenophora (pronounced tee-no-for-a). They are predators that can grow as large as a volleyball and live in oceans all over the world and at various depths, from the surface all the way down to the deep sea.

Cell membranes have thin sheets of lipids and proteins that need to maintain certain properties for cells to function properly. While it has been known for decades that some organisms have adapted their lipids to maintain fluidity in extreme cold — called homeoviscous adaptation — it was not known how organisms living in the deep sea have adapted to extreme pressure, nor whether the adaptation to pressure was the same as the adaptation to cold.

Budin had been studying homeoviscous adaptation in E. coli bacteria, but when Steven Haddock, senior scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), asked whether ctenophores had the same homeoviscous adaptation to compensate for extreme pressure, Budin was intrigued.

Complex organisms have different types of lipids. Humans have thousands of them: the heart has different ones than the lungs, which are different from those in the skin, and so on. They have different shapes too: some are cylindrical and some are shaped like cones.

To answer whether ctenophores adapted to cold and to pressure through the same mechanism, the team needed to control the temperature variable. Jacob Winnikoff, the study’s lead author who worked at both MBARI and UC San Diego, analyzed ctenophores collected from across the northern hemisphere, including those that lived at the bottom of the ocean in California (cold, high pressure) and those from the surface of the Arctic Ocean (cold, not high pressure).

“It turns out that ctenophores have developed unique lipid structures to compensate for the intense pressure that are separate from the ones that compensate for intense cold,” stated Budin. “So much so that the pressure is actually what’s holding their cell membranes together.”

The researchers call this adaptation “homeocurvature” because the curve-forming shape of the lipids has adapted to the ctenophores’ unique habitat. In the deep sea, the cone-shaped lipids have evolved into exaggerated cone shapes. The pressure of the ocean counteracts the exaggeration so the lipid shape is normal, but only at these extreme pressures. When deep-sea ctenophores are brought up to the surface, the exaggerated cone shape returns, the membranes split apart, and the animals disintegrate.

The molecules with an exaggerated cone shape are a type of phospholipid called plasmalogens. Plasmalogens are abundant in human brains and their declining abundance often accompanies diminishing brain function and even neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer’s. This makes them very interesting to scientists and medical researchers.

“One of the reasons we chose to study ctenophores is because their lipid metabolism is similar to humans,” stated Budin. “And while I wasn’t surprised to find plasmalogens, I was shocked to see that they make up as much as three-quarters of a deep-sea ctenophore’s lipid count.”

To further test this discovery, the team went back to E. coli, conducting two experiments in high-pressure chambers: one with unaltered bacteria and a second with bacteria that had been bioengineered to synthesize plasmalogens. While the unaltered E. coli died off, the E. coli strain containing plasmalogens thrived.

These experiments were conducted over the course of several years and with collaborators across multiple institutions and disciplines. At UC San Diego, in addition to Budin, whose group conducted the biophysics and microbiology experiments, Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Edward Dennis’s lab conducted lipid analysis by mass spectrometry. Marine biologists at MBARI collected ctenophores to study, while physicists at the University of Delaware ran computer simulations to validate membrane behaviors at different pressures.

Budin, who is interested in studying how cells regulate lipid production, hopes this discovery will lead to further investigations into the role plasmalogens play in brain health and disease.

“I think the research shows that plasmalogens have really unique biophysical properties,” he said. “So now the question is, how are those properties important for the function of our own cells? I think that’s one takeaway message.” This

Full list of authors: Daniel Milshteyn, Edward A. Dennis, Aaron Armando, Oswald Quehenberger and Itay Budin (all UC San Diego); Jacob R. Winnikoff (Harvard University); Sasiri J. Vargas-Urbano, Miguel Pedraza and Edward Lyman (all University of Delaware); Alexander Sodt (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development); Richard E. Gillilan (Cornell University); and Steven H.D. Haddock (MBARI).

This research was supported through grants by the National Science Foundation, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the National Institutes of Health, the Office of Naval Research, and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Journal

Science

Method of Research

Experimental study

Article Title

Homeocurvature adaptation of phospholipids to pressure in deep-sea invertebrates

Article Publication Date

28-Jun-2024