Roughly 50 families scattered across the world share ultra-rare variants in a particular gene. Silent for years, the inherited mutations make themselves known when patients reach the fourth decade of life. Changes in vision start a cascade of symptoms. Five to 20 years later, the illness is fatal.

Credit: Matt Miller

Roughly 50 families scattered across the world share ultra-rare variants in a particular gene. Silent for years, the inherited mutations make themselves known when patients reach the fourth decade of life. Changes in vision start a cascade of symptoms. Five to 20 years later, the illness is fatal.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have dedicated many years to understanding the rare condition known as retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukoencephalopathy and systemic manifestations, or RVCL-S, with the aim of developing a treatment for it. In a new study, the team reports that a drug approved by the FDA for another condition may stabilize vision for patients with RVCL-S.

“Fifty percent of family members with these genetic mutations will inherit the disease,” said the study’s co-senior author, Rajendra S. Apte, MD, PhD, the Paul A. Cibis Distinguished Professor of Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences. “These families are devastated by this illness, and we have not been able to offer them much hope. However, our new findings suggest that an already approved medication for a different disease may have the potential to help these patients, although additional studies are needed.”

The study is published June 17 in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

RVCL-S is marked by progressive vision loss, cognitive decline, dementia and mini strokes, among other neurological manifestations. In the 1980s, two physicians from Washington University initially linked the symptoms to compromised small blood vessels that cause loss of blood flow to retinal, brain, kidney and liver tissues.

“Imagine a traffic jam,” explained first author Wilson Wang, who paused his medical training to pursue independent research in Apte’s laboratory as part of a program at Washington University. “Small blood vessels are the roads feeding into the circulatory highway system. When blood flow trickles, oxygen and nutrients cannot reach the tissue, and damage ensues.”

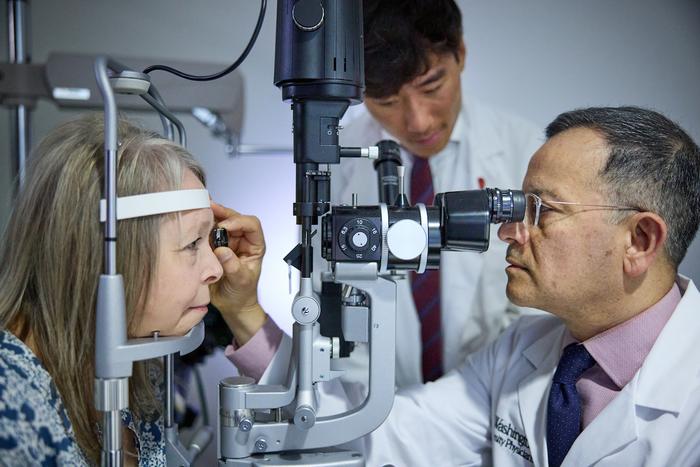

Wilson Wang, a Washington University medical student enrolled in Washington University’s year-long MD5 program, talks with clinical trial participant Patricia Collins before an appointment to check her vision. As part of his independent research project in the laboratory of Rajendra S. Apte, MD, PhD, Wang studied the effect of the drug crizanlizumab on small blood vessels.Other diseases cause similar circulatory system traffic jams. For instance, blockages in small blood vessels are responsible for episodes of excruciating pain in sickle cell disease. Because there is an FDA-approved drug – crizanlizumab – used to help alleviate pain by unclogging congested small blood vessels and preventing blood cells from sticking to the vessel walls in sickle cell anemia patients, co-senior author Andria L. Ford, MD, a professor of neurology and of radiology, launched a clinical trial to test the drug in RVCL-S patients. A collaboration with Apte – an expert in retinal vascular diseases such as diabetic retinopathy and macular degeneration, conditions affecting blood vessels in the retina – focused on patients’ vision, retinal structure and function.

The researchers set out to see if crizanlizumab helps to improve blood flow in the eyes and brain, explained Ford, who is co-director of Washington University’s RVCL Research Center and senior investigator on a parallel study looking at crizanlizumab’s effect on brain lesions in the clinical trial participants.

Eleven RVCL-S patients – who traveled from as far as California despite the challenges of their health and the COVID-19 pandemic – participated in the clinical trial for two years. They received two doses of crizanlizumab in the first month, followed by subsequent monthly infusions.

Images of retinal blood vessels highlighted with fluorescein dye were obtained at baseline and after the first and second years of the study. Wang and Apte, along with colleagues including Dan Spiegelman, a rising third-year medical student, and P. Kumar Rao, MD, a professor of ophthalmology & visual sciences and vice chair of clinical affairs, analyzed the images and compared them with images taken before the patients were treated with the drug. They calculated the amount of space lacking blood flow in a defined region of the retina, a measurement referred to as the nonperfusion index.

After two years on the drug, trial participants saw their nonperfusion indexes plateau, a sign that loss of small blood vessel integrity was slowing, the researchers explained. Routine eye exams revealed that the participants’ vision had stabilized.

Preserving vision in a disease that often ends in blindness has the potential to give patients additional years to read, drive and enjoy activities that bring them happiness. But future studies are needed to test the drug’s ability to slow vision loss in RVCL-S. In a parallel study, the researchers will examine the medication’s impact on brain lesions. If blood vessel blockages in the retina correlate with the brain lesions in these patients, the retina could be used as a biomarker for the systemic disease, Apte explained.

“Until we have a genetic cure, our patients need treatments that halt or slow the progression of the illness,” Ford said. “Washington University is at the forefront of RVCL-S research. Decades of dedication have paved the way for this clinical trial. It represents our commitment to finding treatments that can alter the course of the fatal, rapidly progressing illness.”

Four decades of dedication

Before RVCL-S was identified, patients with the disorder sought answers at Washington University in the 1980s. Seven people, six from one family, were suffering from mysterious neurological symptoms with no known cause. Seven years of inquiry by Washington University physicians led to a published description of the illness, giving their patients a name for their ailments.

Since then, a robust research infrastructure and strong clinical innovation have supported the university’s dedication to understanding and treating the devastating condition.

In 2007, John P. Atkinson, MD, the Samuel B. Grant Professor of Clinical Medicine and one of the key researchers who helped demystify the disease, identified its root cause: mutations in the TREX1 gene. His discovery enabled the development of genetic testing that now gives patients definitive diagnoses. He went on to help establish the university’s RVCL Research Center in 2016, after a $4.1 million donation by Robert Clark and his partners at Clayco – a construction firm in St. Louis – in honor of Clark’s wife who died from the illness at age 50. Two years later, Atkinson led the first clinical trial for RVCL-S.

Although that trial did not show a benefit to patients, the pursuit of treatments for RVCL-S patients has continued.

“We have come a long way with learning about and diagnosing RVCL-S in the last four decades,” Ford said. “But our work doesn’t stop here. More patients have been identified throughout the world, making it possible for other centers to open and bring attention to the rare disease. By working together, we can make a larger impact by increasing the sample size in research studies and finding treatments.”

Journal

Journal of Clinical Investigation

Method of Research

Randomized controlled/clinical trial

Subject of Research

People

Article Title

Crizanlizumab for Retinal Vasculopathy with Cerebral Leukoencephalopathy in a Phase 2 Clinical Study

Article Publication Date

17-Jun-2024