A groundbreaking study has redefined our understanding of early human migration by establishing that the archaeological site of ‘Ubeidiya, located in the Jordan Valley, dates back at least 1.9 million years. This discovery not only pushes back the timeline of early hominin presence in the Levant by several hundred thousand years but also places ‘Ubeidiya alongside Dmanisi in Georgia as one of the oldest known sites documenting early humans outside of Africa. The implications of this finding are profound, revising pivotal moments in human evolution and offering new insights into the dispersal of our ancestors across continents.

The research was spearheaded by a collaborative team of experts, including Professor Ari Matmon of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Professor Omry Barzilai from the University of Haifa, and Professor Miriam Belmaker of the University of Tulsa. Their interdisciplinary approach combined multiple state-of-the-art dating methodologies to overcome longstanding chronological uncertainties that have clouded the age estimates of ‘Ubeidiya for decades. Prior assessments, largely dependent on relative dating techniques, had suggested an age range between 1.2 and 1.6 million years, but the current study decisively extends the timeline.

At the heart of this breakthrough lies the application of cosmogenic isotope burial dating, a relatively novel technique that measures isotopes produced when cosmic rays strike minerals exposed at the Earth’s surface. Once these minerals become buried, the isotopes begin to decay at known rates, effectively starting a natural clock that reveals the duration of their underground burial. This method was instrumental in unveiling a much older age for the sediment layers housing significant archaeological finds, including stone tools and faunal remains.

Complementing this, the team employed paleomagnetic analysis to decode the ancient magnetic signatures embedded in lake sediments at the site. Since sediments lock in the direction of the Earth’s magnetic field at the time of their deposition, these records can be matched with the global geomagnetic polarity timescale. The data confirmed that sedimentation at ‘Ubeidiya occurred during the Matuyama Chron, a geological epoch that began around 2.58 million years ago, further reinforcing the older dating framework suggested by isotopic analyses.

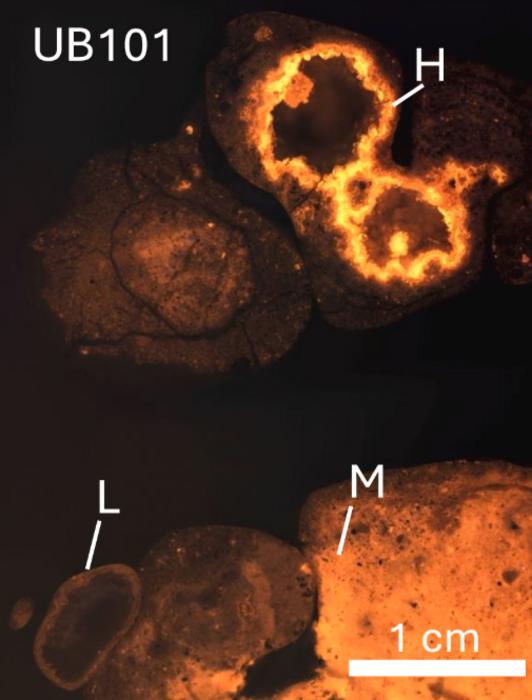

Adding another layer to the chronological puzzle, uranium-lead dating was performed on fossilized freshwater snail shells of the genus Melanopsis found within the site’s sedimentary context. This radiometric dating technique provided robust minimum age constraints for the layers where Acheulean stone tools were recovered. The integration of these three independent dating approaches coalesced into a coherent timeline that significantly recasts the antiquity of ‘Ubeidiya.

The archaeological significance of ‘Ubeidiya is further amplified by the rich cultural and faunal assemblages uncovered at the site. It is renowned for yielding early examples of the Acheulean technological tradition, known for bifacial stone tools such as handaxes. These tools mark a technological leap from the earlier Oldowan stone tool culture, characterized by simpler flakes and cores. The co-occurrence of these tool technologies at the site suggests a complex scenario of hominin adaptation and technological transmission as they ventured beyond African landscapes.

Despite the compelling new dates, the study confronted a significant scientific challenge when initial isotope readings inexplicably suggested ages as old as three million years, a figure at odds with geological and paleontological evidence. The researchers addressed this anomaly by developing a model illuminating a multifaceted exposure-burial history and sediment recycling processes within the Dead Sea Rift system. This insight revealed that sediments at ‘Ubeidiya had been reworked multiple times, complicating straightforward age interpretations.

The phenomenon of sediment recycling is particularly notable in rift valleys like the Dead Sea, where tectonic activity and fluctuating water bodies promote erosion, redeposition, and complex stratigraphic intermixing. Recognizing this dynamic sedimentary context was essential for refining the age models and clarifying the site’s true chronology. It underscores the necessity of deploying multiple independent dating methods to disentangle the complex sediment histories characteristic of ancient loci of human habitation.

This recalibrated timeline places ‘Ubeidiya contemporaneously with the Dmanisi site in Georgia, dating to around the same epoch and marking an early chapter in the global spread of hominins. Such synchronicity strengthens the hypothesis that early humans dispersed from Africa into Eurasia through multiple corridors, swiftly adapting to varying environmental conditions by employing diverse lithic technologies. It also prompts reevaluation of the evolutionary trajectories and interactions among different hominin populations.

Moreover, the findings imply that distinct technological traditions, specifically the Oldowan and Acheulean, may have migrated and coexisted spatially and temporally, reflecting a mosaic of cultural and biological diversity in early human groups. These insights cast new light on the cognitive and ecological flexibility that facilitated early humans in colonizing new terrains, hinting at sophisticated social mechanisms underpinning tool innovation and transmission.

The convergence of advanced dating methods—cosmogenic isotope burial dating, paleomagnetic stratigraphy, and uranium-lead radiometric analysis—exemplifies a paradigm shift in archaeological science, where interdisciplinary integration yields a sharper resolution of prehistoric timelines. Such methodological rigor allows scientists to peel back layers of geological complexity, enabling a more precise reconstruction of hominin history and environmental contexts.

In summary, this comprehensive research advances our knowledge of early human evolution by situating ‘Ubeidiya as a key archaeological landmark that embodies the dawn of humanity’s expansion beyond Africa. It not only revises the age of one of the richest Acheulean sites but also enriches our understanding of hominin dispersal dynamics, tool technology evolution, and the environmental processes influencing sediment deposition and preservation.

The implications reach far beyond regional archaeology, influencing evolutionary biology, anthropology, and geoarchaeology. Through refining the chronology of ancient sites like ‘Ubeidiya, researchers can better map the migratory patterns and adaptive strategies of our ancestors, unraveling the complex narrative of human origins and the prehistoric pathways that shaped our global journey.

Subject of Research:

Article Title: Complex exposure-burial history and Pleistocene sediment recycling in the Dead Sea Rift with implications for the age of the Acheulean site of Ubeidiya

Web References: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2026.109871

Image Credits: Perach Nuriel

Keywords: Isotopes, Archaeology